Support this website by joining the Silver Rails TrainWeb Club for as little as $1 per month.

Click here for info.

This website has been archived from TrainWeb.org/evrailfan to TrainWeb.US/evrailfan.

This website has been archived from TrainWeb.org/evrailfan to TrainWeb.US/evrailfan.

|

The Devil's Carriage Comes to Heavenston |

In

1850, a group of devout Methodists, among

them John Evans, Orrington

Lunt, and Andrew Brown, founded an institution of "sanctified learning"

which became Northwestern University. The site they chose along the

shores of Lake Michigan was at that time part of a rural farming

community known as Ridgeville. They purchased several hundred acres of

farmland, enough for a university campus and a new town. Over the

winter of 1853-54, Philo Judson, business agent for the new University,

laid out the town; the NU trustees named the town Evanston after John

Evans. Knowing the importance of the railroad to the future of the town

and the university, Andrew Brown induced the Chicago & Milwaukee

Railroad to route its tracks near the new town by donating the land for

the railroad right-of-way as well as a depot site [Perkins, 16-22]. Up

until that time public transportation in the area consisted of a

stagecoach that ran along Green Bay Road and took a day and a half to

go from Chicago to Milwaukee, and the ride was not exactly a smooth one:

In

1850, a group of devout Methodists, among

them John Evans, Orrington

Lunt, and Andrew Brown, founded an institution of "sanctified learning"

which became Northwestern University. The site they chose along the

shores of Lake Michigan was at that time part of a rural farming

community known as Ridgeville. They purchased several hundred acres of

farmland, enough for a university campus and a new town. Over the

winter of 1853-54, Philo Judson, business agent for the new University,

laid out the town; the NU trustees named the town Evanston after John

Evans. Knowing the importance of the railroad to the future of the town

and the university, Andrew Brown induced the Chicago & Milwaukee

Railroad to route its tracks near the new town by donating the land for

the railroad right-of-way as well as a depot site [Perkins, 16-22]. Up

until that time public transportation in the area consisted of a

stagecoach that ran along Green Bay Road and took a day and a half to

go from Chicago to Milwaukee, and the ride was not exactly a smooth one:

The directors of the

railroad intended it primarily as a

freight-hauling business; only the railroad's president, Walter S.

Gurnee, envisioned a string of bedroom communities with residents

commuting by train to work in downtown Chicago each day. With that in

mind, Gurnee purchased land along the North Shore that would eventually

become the towns of Lake Bluff, Highland Park, Glencoe, and Winnetka.

Naturally, the passenger stations were sited near the land he owned

[Ebner, pp. 22-3]. The directors of the

road did not share this vision,

however, and at the end of 1855 they decided to cancel the

accommodation trains. Charles George tells us what happened next:

The directors of the

railroad intended it primarily as a

freight-hauling business; only the railroad's president, Walter S.

Gurnee, envisioned a string of bedroom communities with residents

commuting by train to work in downtown Chicago each day. With that in

mind, Gurnee purchased land along the North Shore that would eventually

become the towns of Lake Bluff, Highland Park, Glencoe, and Winnetka.

Naturally, the passenger stations were sited near the land he owned

[Ebner, pp. 22-3]. The directors of the

road did not share this vision,

however, and at the end of 1855 they decided to cancel the

accommodation trains. Charles George tells us what happened next:

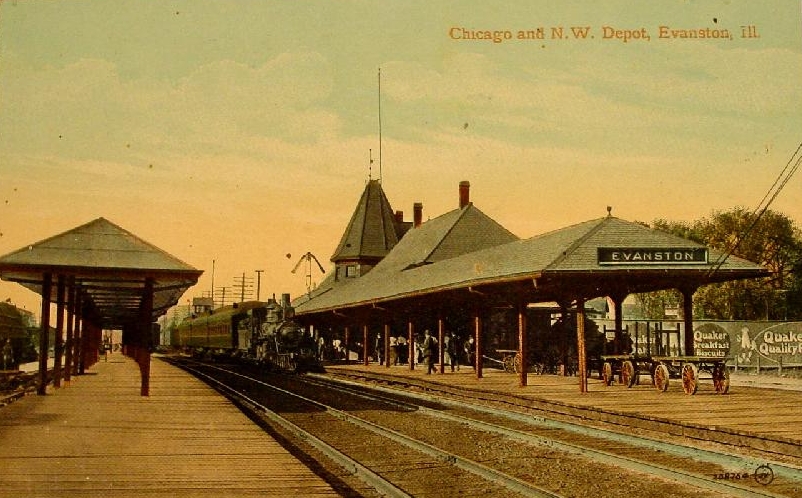

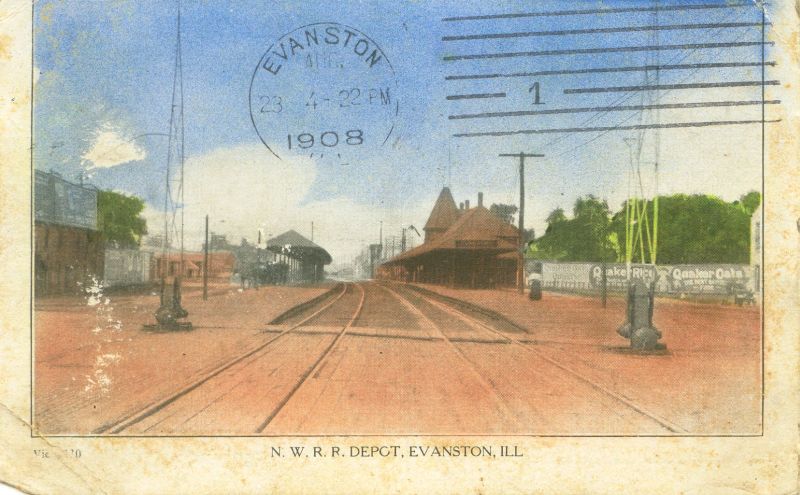

Until 1882 the railroad between Chicago and

Evanston consisted of a

single track. Adding the second track presented a bit of a problem for

the C&NW, which had constructed its stations along the east side of

the track. The second track had to be laid on the opposite side of the

existing track from the stations. For the convenience of morning

commuters, who would obviously prefer to wait for their trains inside a

heated depot, it was decided to run Chicago-bound trains on the left

hand track, since it was nearest to the station houses. This

was, of course, no problem for commuters returning home in the

evenings, who had no need to wait at the station after detraining. This

is the most likely

reason

why the C&NW operated as a "left-hand" railroad. [Knudsen, p. 9]

Incidentally, the "L" also operated

left-handed for a time,

but for a very different

reason: to avoid switching delays on the downtown Loop. [Moffat, p.

198] It switched to right-handed operation in 1913 in concert with

similar changes on the Loop. [Moffat,

p. 242]

Until 1882 the railroad between Chicago and

Evanston consisted of a

single track. Adding the second track presented a bit of a problem for

the C&NW, which had constructed its stations along the east side of

the track. The second track had to be laid on the opposite side of the

existing track from the stations. For the convenience of morning

commuters, who would obviously prefer to wait for their trains inside a

heated depot, it was decided to run Chicago-bound trains on the left

hand track, since it was nearest to the station houses. This

was, of course, no problem for commuters returning home in the

evenings, who had no need to wait at the station after detraining. This

is the most likely

reason

why the C&NW operated as a "left-hand" railroad. [Knudsen, p. 9]

Incidentally, the "L" also operated

left-handed for a time,

but for a very different

reason: to avoid switching delays on the downtown Loop. [Moffat, p.

198] It switched to right-handed operation in 1913 in concert with

similar changes on the Loop. [Moffat,

p. 242]