This website has been archived from TrainWeb.org/italeritrea to TrainWeb.US/italeritrea.

This website has been archived from TrainWeb.org/italeritrea to TrainWeb.US/italeritrea.

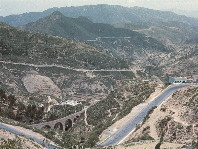

The third class train rounding the mountain above Python Valley

The sun was just coming up that February morning. The fog, though not thick, laid like a blanket between the buildings and the tree tops. I could taste the smell of wood smoke in the cool, damp, still air. Wes and I boarded the post bus and watched a waking Asmara pass by as we road through the town to the far end of Haile Sellassie I Avenue. We got off the bus and walked the last two blocks to the train station.

We paid for our ticket to Massawa and headed for the platform. A steam engine stood puffing quietly on the second of three tracks. Just before the platform the "train" we were taking to Massawa stood on the first track. The single-car train with streamlined silver sides and large flat windows looked more like a trolley car than a train. It was a Fiat Littorina, our transportation.

|

|

Though it was a cool morning, standing in the sun at Asmara's 7600 feet quickly melted any chill so that our wait for things to happen was not at all uncomfortable. Others were gathering too. A young Italian woman arrived with two children in hand. Two Ethiopian students (you can tell them by their books and dull white uniforms) came next. And then a couple of Ethiopian business men arrived wearing suits that told of a culture different from what we were used to. Their khaki pants were topped with white shirts and blue sports jackets. The blue was that of an old, blue car, that odd white-blue that comes from years in the sun.

Finally, a couple of khaki-uniformed guys got on the Littorina. One went to the front, stuck a handle on something, turned a key and a diesel truck motor sound rumbled from the car. Equally distinctive dirty diesel exhaust rose from the top of the car. The engineer twisted the handle and the car moved forward stopping in front of us. We all got in and sat in pleasant leather upright seats that held two people. Thirty-two could sit in pairs of facing seats. Many more could stand. We were only 14 that day.

The engineer sat at a group of controls at the front, like on a bus. Midway, storage compartments jutted into the isle on both sides splitting the 32 seats into equal groups of 16. Another driver's console on the other end sat below the same Art-Deco-styled streamlined windows as in the front. In fact, the "front" and and "rear" of this two-way car were the same. To go in the opposite direction, the engineer took his key and crank from one end of the car to the other and drove from there.

|

|

We sat in the rumbling diesel engine's light, sweet exhaust smell. It sounded more like an idling, semi-trailer truck than a train car. But that was the train car's secret--it was really a two-headed bus on rails.

After a while, the engineer turned the crank a bit, the motor revved, and we began to move. He turned the crank a few more notches and we moved even faster. The clackedy-clack of the wheels against the rails sounded above the motor's dull rumble. We were off. We climbed over a treeless, stony plain. The Littorina actually shifted gears like the bus I knew it was.

Soon our trolley went over a ridge and began down a valley. The sound of the engine died down as we began to gain speed. Then to my surprise (I don't know why because I knew it was working like a road vehicle) the engineer revved the engine, ground the gears into a lower gear, and released the equivalent of a clutch. The car lurched a bit as the engine began to break our descent just like trucks do on steep hills. We seldom got out of that lower gear until we were far below on the flats.

Mai Hizni Valley and beyond

(Debra Bizan Monastery, above Nefasit, is on the far

mountain)

Before long we broke into the great valley of the Mai Hizni (Hizni River) and soon crossed one of the most beautiful stone archway bridges I have ever seen.

My only regret was that I was not up on the road watching us cross. I could almost feel the flow of its gentle "S" curve.

Shortly we passed through the "Porta dal Diavolo," the Devil's doorway, so named by the Italians. What a site! On the left nothing separated us from the floor of Dorfu Valley two thousand feet below. This valley is the first great rent in the earth's crust at the western side of Africa's Great Rift Valley at this point. The wall of the Asmara plateau stands to the left of the valley.

The Americans called this valley "Python Valley" because of the great, winding, dry river bed that snaked down its center. One time I drove my motorcycle down into this valley and along a deteriorated road that passes through the valley to the village of Dorfu at the far end of the valley (See Cycling Python Valley).

Clinging to the vertical side of a low peak, we left Dorfu Valley, made a complete 180-degree turn, and headed back south below where we had been only a short time before. In the middle of a delightfully green eucalyptus grove the littorina stopped for at Dorfu station to pick up and drop off no one. It left as soon as the driver realized the same.

|

|

below where we had been only a short time before." | and its eucalyptus trees |

The trees here and a bit lower around Arbaroba were unusual on this tree-starved mountain complex. The people of Asmara had long since appropriated the trees for firewood leaving a landscape of mostly Prickly Pear cactus. The Dorfu and Arbaroba groves appeared young. It seemed that whoever planted them had the clout to protect them too.

Traveling out and around and back and forth we managed two more 180s before we began winding down the east wall of the Mai Hizni valley. Standing on the road above my beautiful S-turn bridge, you could count five layers of track in this valley.

|

|

above Arbaroba | Dorfu Station |

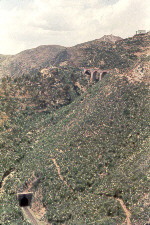

On the east valley wall we wound along the valley edge and in and out of several, small tunnels. At one place the railway crossed the road and then shared the same meandering with the road through another pleasant eucalyptus grove until we entered Arbaroba, a sizeable village clinging to the mountains at a saddle between two ridges. We crossed the saddle to the new ridge's north side. The road took the route along the south side of the ridge.

As our Littorina pulled into the Arbaroba station the third-class train stood on the siding quietly puffing smoke as it waited for us. The damp morning air accentuated the pungent smell of the smoke from its wood-fired boilers. The train pulled several, small, wooded cars, some closed up and others with opened windows filled with people. Other people stood around the train while still others sat on top of the cars.

Each station provided more or less level sidings where a train coming from one direction could wait while the train coming from the opposite direction passed them. That way the railroad was basically a single-track line with passing tracks at the stations.

We picked up two passengers and, once started, began coasting down the mountain again. While I was in Asmara, the Littorina provided first and second class passage while the steam train with its straight, wooden benches provided the third-class passage.

As we descended the northeast side of the mountain this cool morning, a cloud bank filled the distant valleys to a level just above Embatcalla. We continued winding down the mountain stopping at another station far below the road clinging to the ridge above.

We descended through endless terraces of sisal, a crop that once provided hemp for rope but even then had been trumped by the artificial fiber nylon.

The Littorina rounded the side the mountain above Nefasit, made a U-turn, and pulled into the Nefasit station. We sat there ten minutes while the driver disappeared with his operations crank into the station. As we waited, two camels loaded with wood plodded down the adjoining road behind their driver.

Moving down the mountain again, now at a gentler decline, we actually heard the groan of the engine pulling us now and then rather than constantly breaking our descent as it had above Nefasit. Staying just above the road, the railroad followed the road down the long Nefasit valley. Several stone bridges gracefully spanned the inner end of side valleys to allow the route to turn easily.

At the end of Nefasit valley we entered the cloud bank as a bridge crossed the road and guided us into Embatcalla valley.

After a quick stop at the Embatcalla station, we continued down the valley through the clouds. By the time we crested the hill above Ghinda, the thin cloud layer, now above us, provided a uniform gray sky.

As we pulled into the Ghinda station, several vendors approached the Littorina with refreshments. A woman in a dirty shamma (the native white dress) offered tangerines in a woven basket. Another woman offered oranges. And yet another, boiled eggs. A small girl carried a large brightly colored, patterned bowl filled with what looked like the puffed wheat I ate for breakfast as a kid. Maybe this was their version of popcorn.

|

|

| |

|

I bought three tangerines for ten cents Ethiopian (four cents US) and sat back to enjoy these sweet, tasty fruit grown locally on some Ghinda valley farm.

The road and the railroad diverged at Ghinda. The road plunged east over the mountain side to the plains known as the "flats," "flats" because though it had some hills, the generally flat land so drastically contrasted with the mountains we had passed through from Asmara. The railway took a longer, round-about, southerly route down a long valley and then out onto the plains making for a gentler, more manageable grade.

At the bottom of the descent, we entered the wide, flat, Damas River valley. At one place the railway actually went four or five kilometers in a straight line. Several well organized farms stretched away from the tracks in both directions.

After a stop at the Damas station, we moved on clackedy-clack and soon began descending back and forth several times as we entered the area of thorny acacia shrubs and rocks around Dig Dig and beyond.

The Mai Atol (Atol River) station sat amid a small village of mud and wattle houses. A man in the station doorway held his goat by its leg to keep it from running away. Below here we rejoined the road, following it most of the rest of the way into Massawa. By this time the route was moving through rolling hills and generally flat desert waste lands below 600 feet above sea level with several kilometers to go to Massawa.

At the road's 86 kilometer marker (I don't remember the railroad's marker) a stone bridge crossed a dry river bed--nothing unusual, tens of stone bridges cross tens of dry river beds along the railroad. But this one was different. Members of some Eritrean liberation movement had blown up this bridge earlier. Being resourceful, the railroad engineers had just moved the tracks to the right of what remained of the bridge and laid them through the river bed. I suspect their thought was that whenever the once-in-ten-years rain washed the tracks out, they'd take the time to replace them. Until then they'd work quite well in the river bed. We eased into the river bed, glided past the bridge, groaned up the other side, and continued across the plain. No big deal.

The next stop was Saati, the site of an abandoned Italian fort where, in 1887, Ras Alula made an attempt to stop the Italian intrusion into Eritrea. Though that battle was successful for Ras Alula, he lost the war.

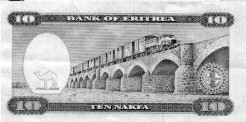

After more rocks and acacia shrubs, we came to a broad, dry river bed crossed by a long, arched, stone bridge, an impressive span--even over a river of sand. Many years later after they had won their independence and had begun to rebuild the then defunct railroad, the Eritreans celebrated their railway ingenuity on their new Ten Nakfa note: they showed a truck pulling a train across this bridge.

Train crossing the same bridge

on the back of the new Eritrean ten Nakfa note

the Littorina soon stopped at the Adi Berai station in a vast village of one-story, mostly concrete, buildings on the coast next to the Massawa islands. We stayed in the station a long time while the engineer stood around talking with other khaki-clad railroad types. The heat was oppressive (above 100 degrees) and the flies were impossible. I was very ready to go the last four or five kilometers.

Eventually, we crossed the long causeway to Talud, the first of the two islands that make up Massawa proper. Our trolley pulled into Massawa's Talud Island station, a station only a bit cleaner and spiffier than the others along the route. We left our little Littorina for a weekend in the 120-degree, dry heat of Massawa.

Later in the day we watched a small engine moving cargo around the port. Not even big enough for the engineer to stand up straight, the little engine tooted and puffed its acrid, wood smoke as it moved in and out of the Massawa port.

For more examples of the train in Massawa, see the Massawa chapter of this book.

The tracks are 950 mm apart, a size unique to the Italians. According to the 1952 200 Pagine sull' Eritrea, a book showing off the commercial wares of Eritrea, the line had 29 stone bridges, two metal ones, and 39 tunnels and 11 Littorinas and 23 steam and diesel locomotives provided its pulling power.

After the time I was there but surely part of the overall story, the Ethiopians dismantled the route in 1976 when it became apparent that they could not keep it running due to Eritrea's war for independence. Since Eritrea achieved independence in 1991, the Eritreans have been slowly rebuilding the route. They hope to reach Asmara in 2002.